The actor who refused to act in front of the killers

By: Miljenko Jergović (published in Jutarnji List, on June 26, 2010)

Translated by: Jelal Fejza

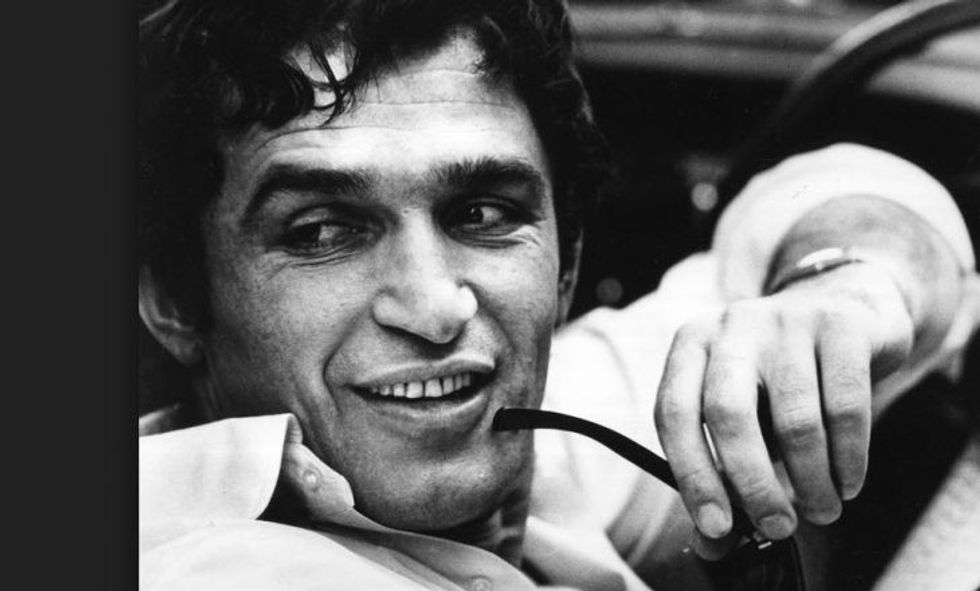

Bekim Fehmiu was a sex symbol, he was Albanian, although an actor in foreign languages, he was an artist who belongs to both peoples.

Books Brilliance and horror one day he will be very important and famous, while Serbian culture and literature have to honor the fact that in the period of its horror, an Albanian wrote a redemptive work. Homeland Serbia will be proud of Bekim.

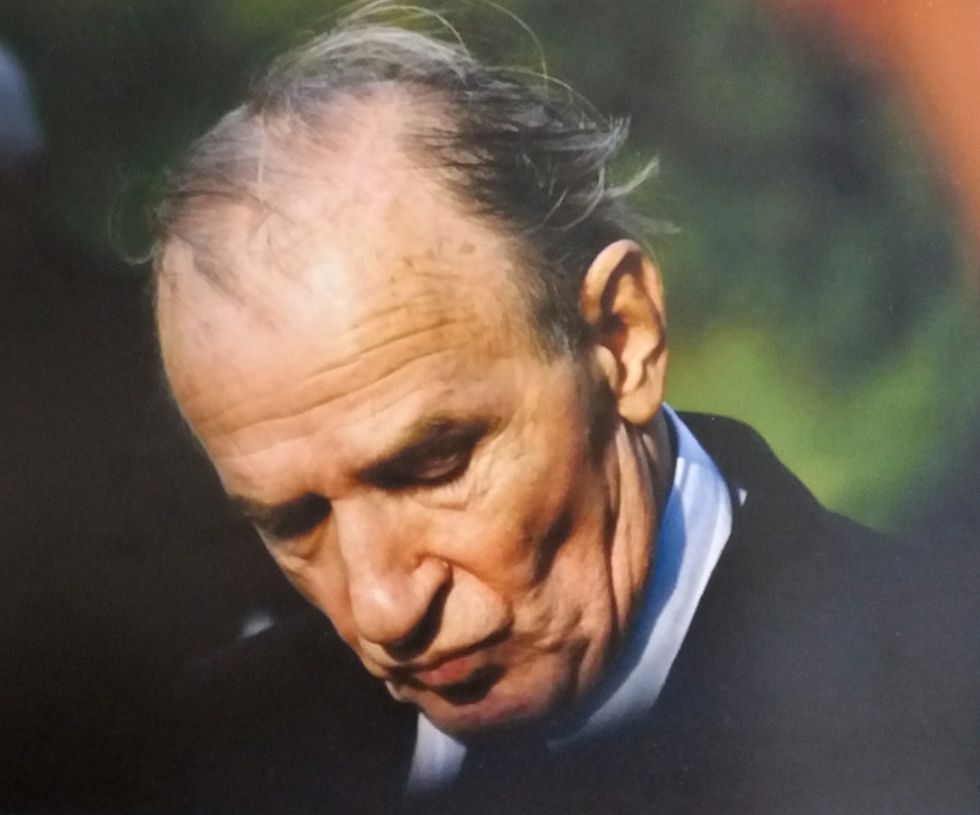

In 2001, in the art gallery Velkovic on Birçaninova Street in Belgrade, I met Branka and Bekim. She: a great theater actress, a fine and delicate lady from Belgrade, on whose face that evening there were no traces of the hard times and unpleasant circumstances in which she found herself. Him: for more than a decade out of the public eye, for protest, with a face that looked different from the one we have come to know through the movies. He had aged beautifully, but in the meantime the face of a sex symbol of Yugoslavian and European cinema had transformed into the face of an ascetic. If Ahmed Nuredini had managed to age, or rather if Mesha Selimoviqi had aged his character, Bekim Fehmiu would have been very suitable to play him in the film. But, for sure, he would not play it, because Bekimi had decided, first of all to protest because of the relationship to the Albanians in Belgrade and Serbia, and then also for many other things of this type, not to act anymore.

Once, many years later, I asked him about it, and he explained, in an argumentative and calm manner, that acting to him is a game, a very serious game indeed, but he can't play anymore after those terrible things. that happened. He spoke easily and beautifully, as if he knew how to speak, as if every time he was learning this language of ours, which was a foreign language to him. He treated every word very carefully, as if he were a human being. He spoke with a beautiful voice, a voice that you have had since birth, but in a sense you have to deserve it. It didn't have that hint from the actor, who is charming anyway. He was clearly a dignified man, only that it was not the dignity of those series from English films, or those icy scenes of civic life according to Bergman. His dignity was composed of warmth and acceptance.

Honestly, but only once, I told him how much he had meant to me when I was a child. I didn't want to look like some teenager who has just met a famous person who has always been in front of his eyes on the poster attached to the wall of his childhood room. He was amused when I told him that my grandmother could not see that movie scene when Beli Bora breaks the glass in half and then, out of spite, trembles on top of the glass pieces. Some things in that movie seem much more real than they might be in life.

Bekim Fehmiu spoke the Serbian language as well as other languages as we speak them. But it would be a mistake to say that the pronunciation betrayed him, because his pronunciation was always correct. But his intonation was different, the rhythm of his words was also different. The staccato of his phrases expressed in the Croatian, Serbian, Montenegrin or Bosnian language has entered the cultural memory of a country and a time. This is how Bekim spoke and it is a mistake to think that this is so because the above languages were not his mother tongue. In the manner of speaking of Bekim, his personality was embodied, that of the actor and that of private, so that an entire era, the greatest and most important of all eras in the history of mankind, the era of our childhood and adolescence, it wouldn't have its harmony if Bekim Fehmiu didn't speak like that.

In the movie Special education directed by Goran Markovic, he played the role of the educator Munixhaba. Yes, I know it's a funny adjective, this is how the actor expresses himself in one of the first lines of the film. In this film he played the role of a strange, powerful and self-raised man, so it is not surprising that the obituaries, when writing about Bekim, mentioned so much precisely Special education. In his case it was a film like it happens with all other actors during their careers and this is known only when their career is at the very end, at the time when they gather and say their last goodbyes. Some shot the film Testament at the end of their career, others at the beginning, while Bekim Fehmiu shot it somewhere in the middle.

In 2001, I returned to Zagreb with the first part of his biographical prose Brilliance and horror. I started reading it on the train and read it slowly for three nights in a row. Although the Belgrade press wrote respectfully about this book, and it was quite nicely written two or three times in Zagreb, its greatness and inner intensity remained outside the public discussion, for some future time perhaps, at which time to be able to read more calmly and patiently. It seems like they recognized its importance and therefore put it on the bookshelf for later reading.

Bekim Fehmiu tells about his life as a child, since he was born in an Albanian family from Kosovo in good economic condition, in the years of the Second World War. Slowly, word by word, figure by figure, he puts together a mosaic that surprises the reader first of all with the high degree of stylization. Although in this stylization there is no one who can be sick in the way of Marcel Proust, this prose, in terms of finesse and sensitivity, but also for the environments of old-time lordships, is a certain Kosovar order after the lost times. But apart from that book Brilliance and horror, can be read as a great novel about the growth of a man, which takes place anywhere, in any known or unknown part of the world, it is a book from which the Yugoslav reader, and in particular the Serbian one, for the Albanians and family life in Kosovo, receives more information than it received during the past ninety years, years in which they lived in the same country and where they had the opportunity to read newspapers, magazines or books published in our languages. And, all this with awareness of the dignity of both the human being and the literary text. Because, for Bekim, this was the same morality, because he simply could not have two morals. Therefore, it was so difficult.

The narrative ends in the time before the main character becomes an actor. I asked him if he will continue. Oh, yes, of course! And every time I met him and Branka, or just Branka, because I never saw him without Branka, which for me is a sign of great love, I asked him what happened to the second part. I asked them because I was interested, but also because on the other hand I knew that it is very important for the writer to be asked such questions. It was supposed to be a sign of my respect for the writer at Bekimi. Really great writer.

Deciding not to play anymore, Bekim Fehmiu condemned himself to loneliness. The worlds and identities that arose around him during and after the war were not his own. He lived in love and loneliness. Who knows when and which of these two is the greater. My problems with not belonging and with it my identity, many times less dramatic than his, and the moral role, which compared to his is insignificant, which lead me precisely to the one and the loneliness, often I solved them with the Blessing in mind. Those who continue to play regardless of the circumstances should not be criticized, but it is vitally important for a person to be able to marvel at the actor who refused such a thing.

In the first days of the spring of 2009, a message from Branka and Bekimi came to my e-mail address, with the manuscript of the second part of the book attached. Brilliance and horror. They asked me to read it, help them with a doubt of a private nature, and tell them honestly what I thought about the text. I printed the book and read it very quickly, but it took me two months to get back to you. A great story, quite different from the first, but still excellent and terrible, poured into me, and therefore I wrote to them that they should publish it as soon as possible. He was happy. The real writer, unfortunately, never knows that he has written a beautiful book, so he needs someone to tell him.

At the end of the novel, he describes how the war began: "Evening. The sky is orange-grey. Church in Graçanica. People go in and out of it in convoy. Kiss the icons. Black crows fly in the dome of the church. Above them, another flock of crows, flying and cawing, circle, making the sky seem even blacker. On the horizon a blood red furrow separates the land from the horizon. The cawing of crows over Graçanica is suffocating. Night. I stand on the wide terrace of Dije's house. Not a leaf moves. Down there, in Tauk's garden, five members of the special units. I only see their cigarette butts that light up when they inhale the smoke. From a distance comes a smell of sulfur. Nitrogen plant. A heavy and strange silence lies over the city! The brilliance was dulled”!

There is something divine that will one day be understood, and I know very well that it has to be understood, because otherwise there is no way it can be, that the two greatest redemptive books of Serbian literature of the beginning of this century have written precisely by an Albanian.

Bekim Fehmiu died of his own accord. His desire was much stronger than this world. And we must again respect this wish of the Blessing. All his loneliness poured into love.